Quantum computing for lawyers

and anyone who’s not sure what “quantum” means

Last week I had lunch with a lawyer friend:

– So tell me, what’s this quantum thing about?

– You mean quantum computing?

– That scary thing in the news.

– Quantum computing.

– So explain it to me.

I then remained silent for thirty seconds, as I always do when someone non-technical asks me this. I looked for an angle that wouldn’t insult her intelligence or distort reality, and without the lazy analogies you hear on YouTube.

My friend is brilliant, but knows nothing of quantum physics or algebra. Instead of jumping into technicalities, I found that what works well is saying what QC is not, starting from the familiar misconceptions. But before that, I must clarify the meaning of “quantum” and “computing.”

Trigger warning: To physicists and quantum engineers: there may be wince-worthy simplifications. If you catch anything blatantly wrong or misleading, call me out and I’ll fix it.

Disclaimer: Not all lawyers are clueless about quantum computing. Another lawyer friend, after seeing a draft of this post, suggested I start with: “The first thing it’s not is ‘in existence.’” I happily complied.

Quantum

In quantum computing, “quantum” refers to quantum mechanics a.k.a. quantum physics, which explains how small particles behave: photons, electrons, and so on. The rules down there are nothing like those that govern planets, rocks, and basketballs; gravity matters very little, for example. Instead, weird and counterintuitive rules apply, like:

Particle–wave duality: A quantum object behaves both like a particle and a wave, depending on how you look at it. As a particle, it shows up at a specific place; as a wave, its position is not pre-determined but described by probabilities. And waves can add up or cancel out, like sound waves in your noise-cancelling earphones—that’s interference.

Entanglement: A quantum state can involve several particles, for example multiple ions. Observing one particle can tell you what you’ll find when observing the others, even if they are light-years apart.

Randomness: Colloquially, we call events random when they’re hard to predict, even though they follow deterministic (that is, non-random) laws, like a coin toss does. Quantum mechanics involves genuine, non-deterministic randomness.

Terminology footnote

Physicists borrowed the word “quantum” from Latin, plural “quanta,” to mean a discrete amount of energy, time, matter, or other physical concept. In physics, a quantum is the smallest relevant unit within a given theory. A common misunderstanding is that quanta are necessarily indivisible*, whereas they’re not always:

Photons are (essentially) indivisible energy quanta in the context of electromagnetic fields. However,

The nucleus of an atom can be treated as a quantum in the context of nuclear physics, even though it’s made of smaller parts: protons and neutrons, themselves made of quarks (indivisible).

*A particle is indivisible if it’s not [known to be] made of other parts. The known-to-be, generally accepted understanding is called the Standard Model of Particle Physics, or just the Standard Model.

Computing

Computing is the business of turning the input of a program into its output. In today’s computers, input and output are bits (ones and zeros), but in principle they can be described in many other ways, like bigger numbers or other symbols, or dog barking.

A program describes the operations the computer applies to the input. It’s usually in a human-readable language like the Python or Rust programming languages, which another program—an interpreter or a compiler—translates into computer-level operations: arithmetic operations (addition, multiplication, etc.), logical operations (AND, OR, etc.), or memory manipulation (data copy, erasure, etc.).

Quantum computing (theory)

Physicists came up with quantum computing because they were stuck: classical computers weren’t powerful enough to simulate the behavior of small particles in order to test physics theories. Instead of simulating Nature’s fabric with electronic computers, they figured they could work with the real stuff they want to simulate, directly obeying the very laws they’d have to simulate with transistors.

QC was first imagined by Richard Feynman in the papers Simulating physics with computers (1982) and Quantum mechanical computers (1985). Rather than manipulating bits with electronic circuits and transistors like classical computers do, QC manipulates quantum states, much smaller and brittle stuff. This means that

Input and output are encoded as quantum states—remember, the things made of quantum objects, which behave “randomly” and interfere with each other because they’re kind of waves even if they’re called particles.

Programs transform quantum states, rather than bits or numbers. These operations are totally different from your CPU’s addition or multiplication: simplifying really a lot, quantum operations—quantum gates—change the probabilities** underlying quantum states; they change the level of uncertainty, they may turn uncertainty into certainty, or the other way. If you wonder what this has to do with computing, worry not.

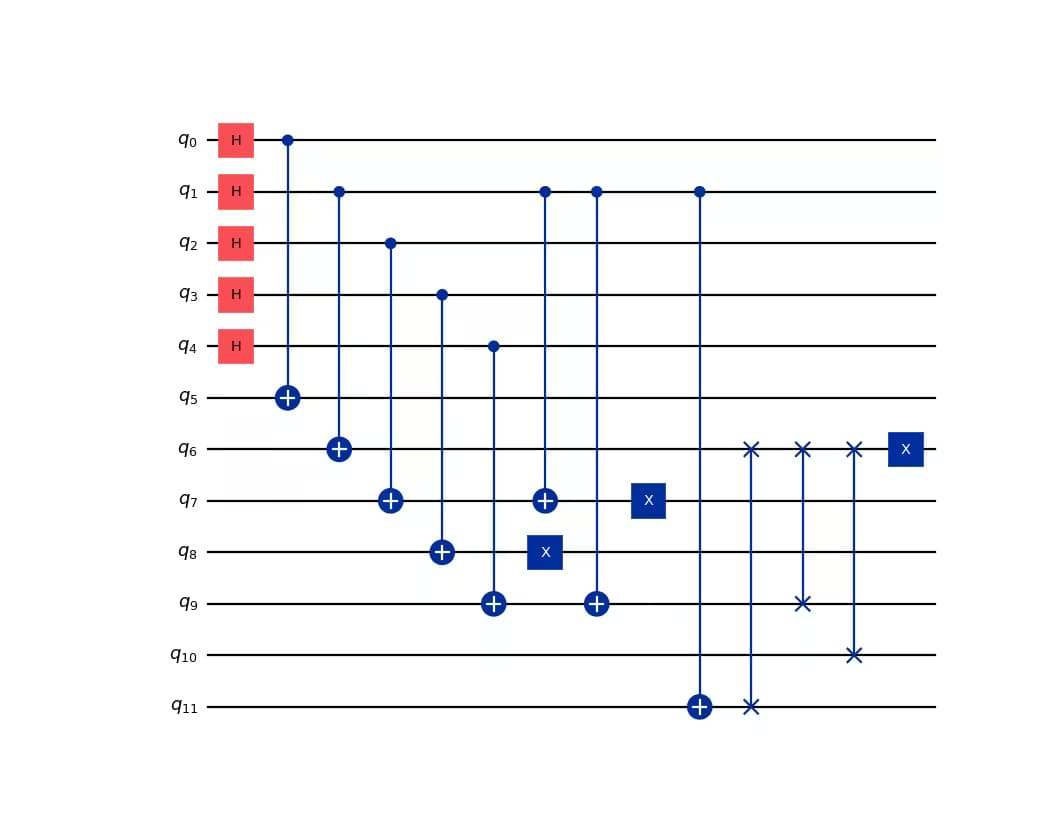

On paper, a quantum computing program looks like a circuit: objects connected by wires to quantum gates until a final state from which you observe the output, not unlike an electronic circuit:

(Image courtesy of IBM.)

**The probabilities aren't exactly the probabilities you’re used to, like a 50% chance, and generally a decimal number between zero and one. Quantum probabilities are called amplitudes, and are complex numbers (of the form a+bi, where i is the imaginary unit), and can be negative.

Quantum computers (practice)

As previously stated, (useful) quantum computers do not exist yet.

Building and running a quantum computer is way harder than building a microprocessor like the one in your phone. You’re not doing electronics, you’re doing physics: you don’t deal with bits represented as transistors (electronic components) but with quantum bits (qubits) materialized by literally the smallest particles in the Universe. Because they’re minuscule and brittle,

Qubits are extremely hard to create, set in the state you want, manipulate, and get to interact with each other. I won’t elaborate on what “hard” entails, but as you imagine it’s about challenges in terms of science, engineering, logistics, equipment, lab environment, raw material, etc.

Qubits are highly sensitive to their environment: heat, electromagnetic fields, acoustic vibrations, and so on. You need to reduce the temperature to close the the minimal possible (zero Kelvin) and implement quantum error-correction techniques to keep the system stable and error-free.

Several companies try to build quantum computers, but after decades of research and billions invested there are only tiny prototypes that—despite what the websites and marketing material and press releases say—are of no practical use whatsoever.

Let me emphasize: None of the current quantum computers prototypes by IBM, Google, or any other company is superior to a modern classical computer, for any reasonable definition of “superior.”

Now tet me do an admittedly unfair and misleading, but not entirely pointless comparison:

A modern laptop can often store a terabyte of data (around 8000 billions of bits) and has a working memory of dozens of gigabytes (billions of bits). Its microprocessor can run computations lasting days, weeks, and more long as it’s kept powered.

Today’s best quantum computer prototypes are limited with respect to:

Qubits number: Around a thousand qubits, of which only a handful can serve to actually compute, because of the…

Error rate: The higher, the more qubits you need to correct errors, with quantum error-correcting codes.

Coherence time: Quantum computers remain stable (and thus usable) only for a time ranging from microseconds to seconds.

Different QC technologies make different trade-offs between those three dimensions, but none currently comes close to satisfying all three.

What QC is not

The word “quantum” sounds cool, scientific, and mysterious, which is precisely why it’s been overused in pop culture and advertizing to suggest some science-backed miraculous technology, from dishwasher tablets to cosmetics. Because quantum computing is actually quantum and poorly understood, it’s a bonanza for hyperbolic and grotesque claims. Even otherwise respectable companies lower themselves to clickbaity statements, which are amplified and distorted by the content generation industry: Google alluded that its QC research supported the many-worlds interpretation (a.k.a. “multiverse”) of quantum mechanics, while Microsoft claimed to have created a “new type of matter.”

More subtle—and arguably more irritating, and dangerous—are the falsehoods that aren’t outright nonsense. These are the intellectually tempting, audience-pleasing distortions plaguing news sites and YouTube videos, often spread in good faith by experts from adjacent fields. Let me highlight the most common ones:

Myth 1: Free parallel computing

A quantum bit can be seen as (oversimplification warning) being “1 and 0 simultaneously,” in the sense that observing it yields 0 or 1 according to some (quantum) probability parameters. This at-the-same-time-ish state is called superposition.

Wait, if a qubit can be in many states at once, why not create a state that represents all possible solutions to a problem and run the computation once to let the quantum computer find the one that works? We could try all passwords simultaneously and select the correct one at the end!

Sorry, it doesn’t work that way. Not even close.

This misconception is so common that Scott Aaronson (among the greatest QC researchers and bloggers) added it to his blog’s banner:

Myth 2: Ultra-fast computers

A QC’s power (we’ll get to it) has nothing to do with speed in the usual sense of velocity. QCs are not classical computers doing the same operations orders of magnitude faster. In fact, if you count raw operations per second, a quantum computer would almost certainly be slower than a classical one.

Myth 3: “Cracking” all cryptography

A corollary of Myth 1: Many cryptographic systems rely on a secret key. Take data encryption, as used to encrypt a database: anyone who knows the key (and has access to the encrypted data) can decrypt it and recover clear text data. Could a quantum computer “crack” such encryption by trying all possible keys at once? No. QC can’t improve on bruteforce, save for a mostly theoretical speed-up.

However, there’s another class of cryptography that quantum computers could break:

Why all the fuss about QC then?

At last, let’s address my friend’s concern:

Why does QC matter for cybersecurity?

Why has U.S. Federal agency NIST standardized a new type of public-key cryptography that is “post-quantum”? And why has it retired the RSA and elliptic curve-based cryptosystems?

Why are cryptocurrency users worried? (And why quantum computers will not steal your bitcoins, even if they can?)

Quantum speed-up

By exploiting superposition, interference, and entanglement, quantum computers could solve certain mathematical problems far faster than any known classical computer; again, not by running the same instructions faster, but by doing (quantum) things that non-quantum computers can’t do.

This is called quantum speed-up. And in some very specific cases, problems that would take classical computers millions of years could, in principle, be solved in days or hours on a sufficiently large QC.

(For a list of quantum algorithms offering quantum speed-ups, check the Quantum zoo.)

Unmultiplying numbers

Most encrypted communications, from WhatsApp discussions to the HTTPS connection to this blog, use public-key cryptography, whose security relies on the difficulty of deceptively simple math problems. One such problem is factorization, or “unmultiplication”: any computer can easily multiply numbers, even very large ones. But they can’t do the reverse operation:

For example, my computer can multiply

40160895852844009921030582458177023751149608603560122736811850395290758101622602227312993008663060573128309806075822160041568801528700271189810757373385118277329108717034617301346931111565786388668586110756276252344613018958475585818678689475264694034888916262136204857616135787294991955010950534715362928961

with

167490607764457115789922096379820718444546728581554589725893099248994268739022303883547106856890629039527872559871857553049463569835676624582299213536348554005121105980941986448170586253727274865993644246974524181147667338383488542450160330541384660724752104687618042059153685486425499029405656789170161284103

and obtain

6726572854757908509192009735316226908350181862868328529931455243588748157623532254497231332747122156614053064156389626106224601390887852274333723141725274232300258425373923736794992336313639711325862458921610845776982386791554679218228917337362619041703342861211862884349013870563321829893198881132168561777205652311559741549923492808959528563944472756679353515749423685198959573829938226017454631095212636707498919070513249730513598379520705705891364183849743691218116470125737479401662245891972047284236561716637900527887566791393045934340156835783212647076267119945090108260675835377686382014735001822686927606983

Given this number, however, no computer can recover its two factors. But a quantum computer could, using Shor’s quantum algorithm. And this would literally break most internet communications.

When?

In theory, given enough time, research, engineering effort, and funding, it should be possible to build a quantum computer that’s large and reliable enough to run Shor’s algorithm and break the public-key cryptography used in practice. We simply don’t know when or even whether this will ever happen.

Many quantum computing companies will tell you “five to ten years.” I don’t expect to see such a machine in my lifetime (though I’d be happy to be proven wrong.) I’m not dismissing the risk, just weighing the evidence the way a lawyer would.

Featured image: Better Call Saul.

Keep an eye out. Well done on the article. 👍👍👍

I was horrified to see a QC firm working really hard, just to be able to simulate a simple 2-state binary architecture. We will end up with nothing useful, except the total elimination of cryptographically protected communication.