DFW

An aesthetic shock

As my literary mentor Juan Asensio says, you don’t read—and appreciate—great writers and great books by gradually maturing from average writers and average books to superior ones. It takes a revelation, an aesthetic shock, an encounter with a writer where you feel this is different. You’re no longer consuming a product from the book industry, but reading timeless literature. And after that, you can no longer read average, let alone mediocre books.

I experienced this in my early twenties when I first read Léon Bloy (via a friend on some indie hip-hop forum who shared a link to his journal, hosted on a Project-Gutenberg-like platform), and later, in 2006, with Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (via Juan). This post is about another writer I’d call a genius if the term weren’t so cliché and cheesy.

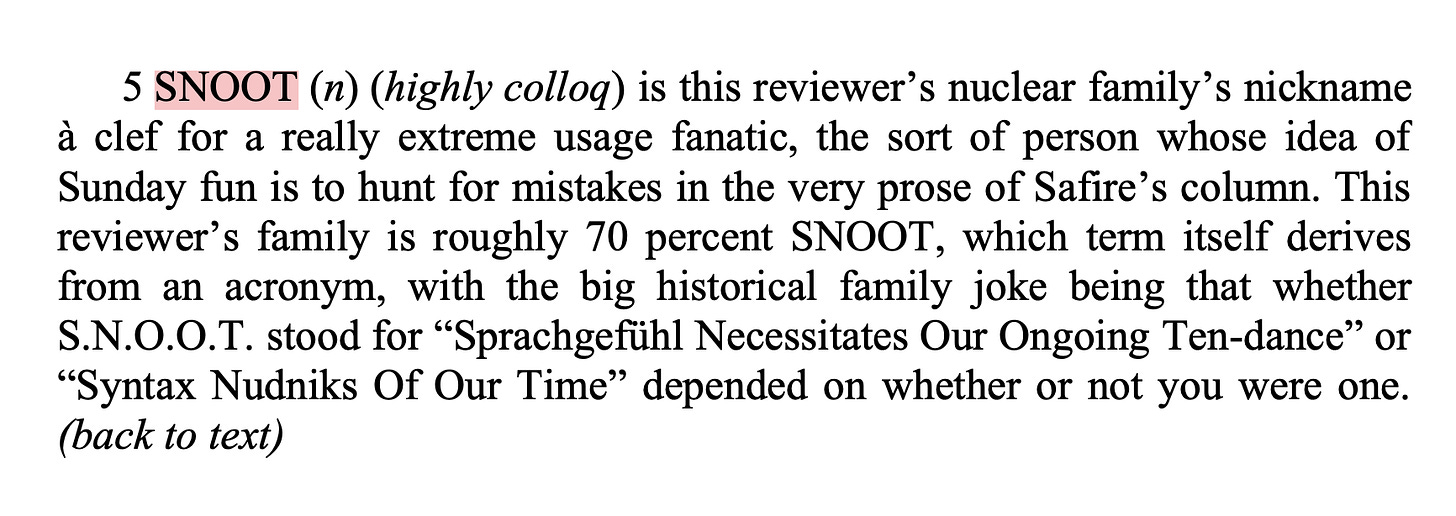

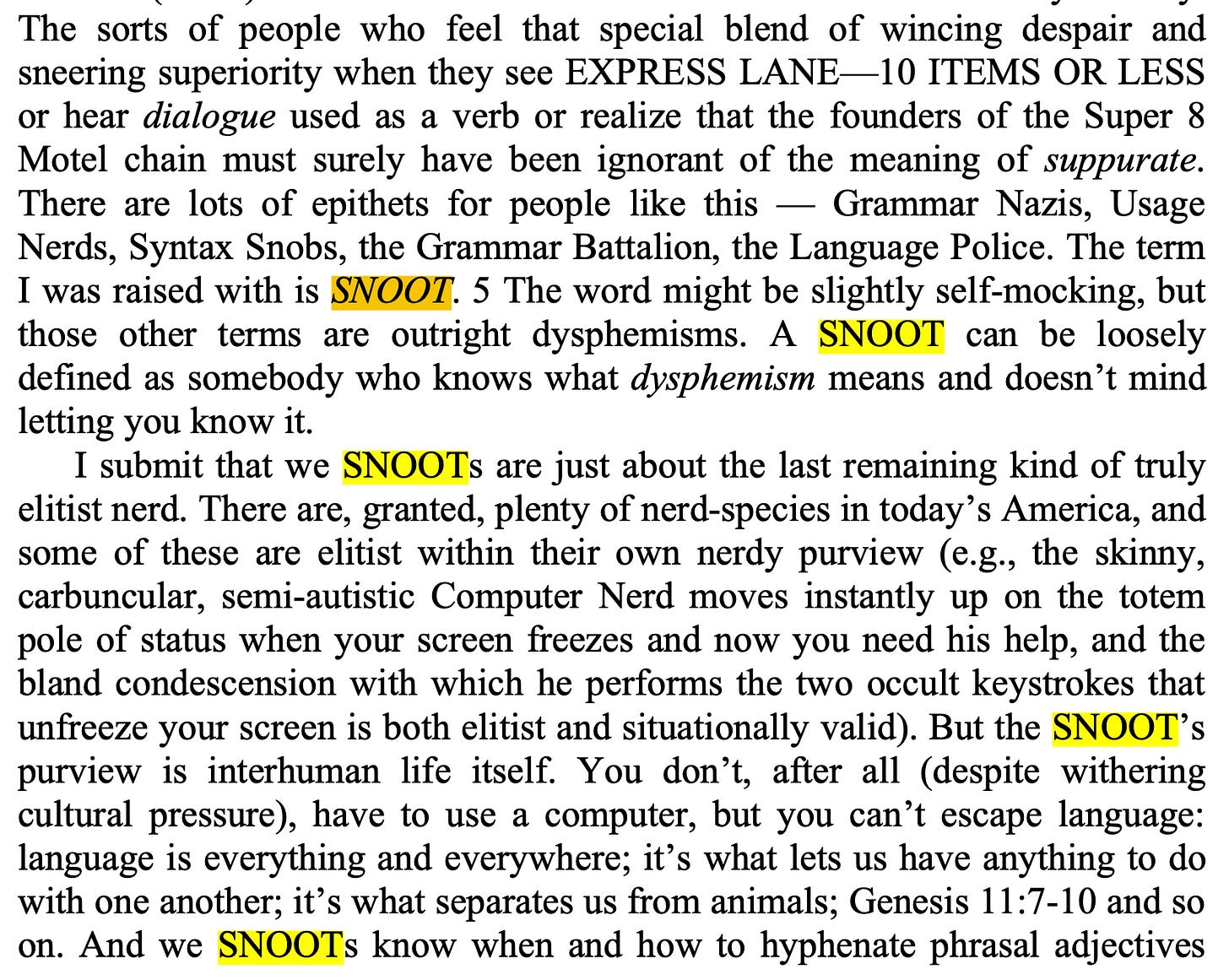

OK, shame on me. I had never read the late David Foster Wallace until three weeks ago, even though Infinite Jest had been sitting on my shelves for a year or so. Since then, I’ve been binge-reading his essays and realized I hadn’t taken this much pleasure in reading in years. The mix of wit, erudition, humor, modesty, Midwestern folksiness combined with his quirks—footnotes of footnotes, nested parenthetical statements, third-person self-references (“your correspondent”), post-postmodern irony, his I-trust-the-reader non-introductions of abbreviations and acronyms, his SNOOTness (see below)—makes his prose highly enjoyable, refreshing, and often hilarious.

On said SNOOTness, from Authority and American Usage, which sent me down the rabbit hole of prescribers vs. describers and into Gardner’s Modern English Usage, whose introduction debates the issue at length and cites DFW:

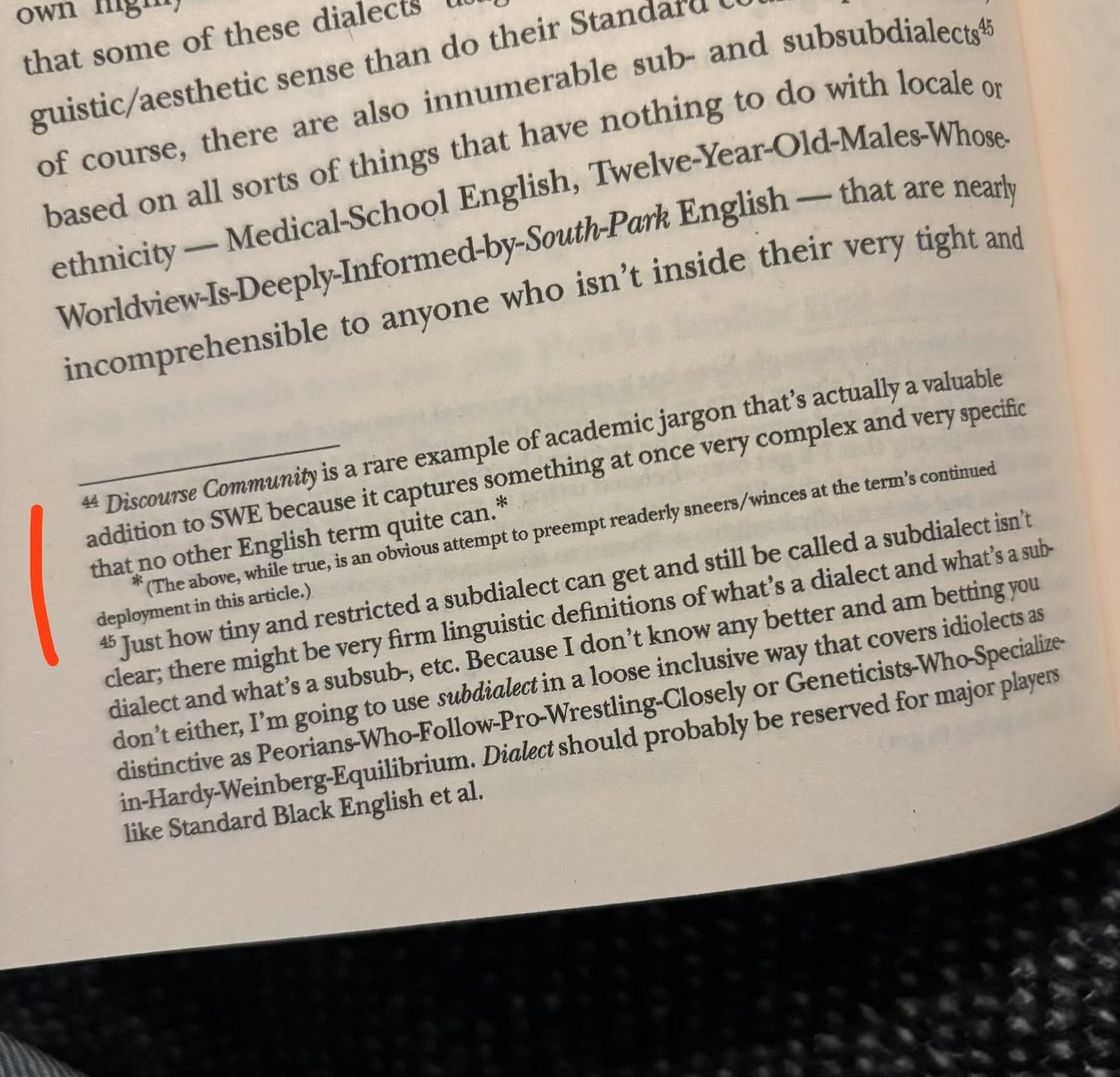

If you’ve never read him, this gives you a taste of DFWism. And here’s an example of a meta-footnote (from the very same essay):

I initially wanted this post to be a ranking of my favorite essays of his—influenced by internet tier-list culture—but quickly realized this was 1) a bit silly to begin with, 2) unfair, since I haven’t read all of his essays, and 3) even setting #1 and #2 aside, nearly impossible, because all the essays I’ve read so far are brilliant, unique, and on vastly different topics. As an evidence, a cursory online search led me to a Reddit thread asking readers for their favorite DFW essay, and almost every response was different. I’ll just say that Consider the Lobster, perhaps his most famous—and admittedly most accessible—essay is objectively not the greatest, even though he did choose it himself as the title of his second essay collection, published three years before his death.

Instead, I’ll just

Encourage you to read his essays (and novels), some of which are available online, and to listen to the recording of his 2005 commencement speech (later published under the title This is Water), and to this 2004 conversation.

Encourage you to watch his interviews, most notably the 1997 ~30min one with Charlie Rose and the 2003 ~84min one for ZDF.

Share a glimpse of his style, his observational superpower, his attention to minute yet meaningful details, his narration, his earnestness, his humor. See the excerpts below:

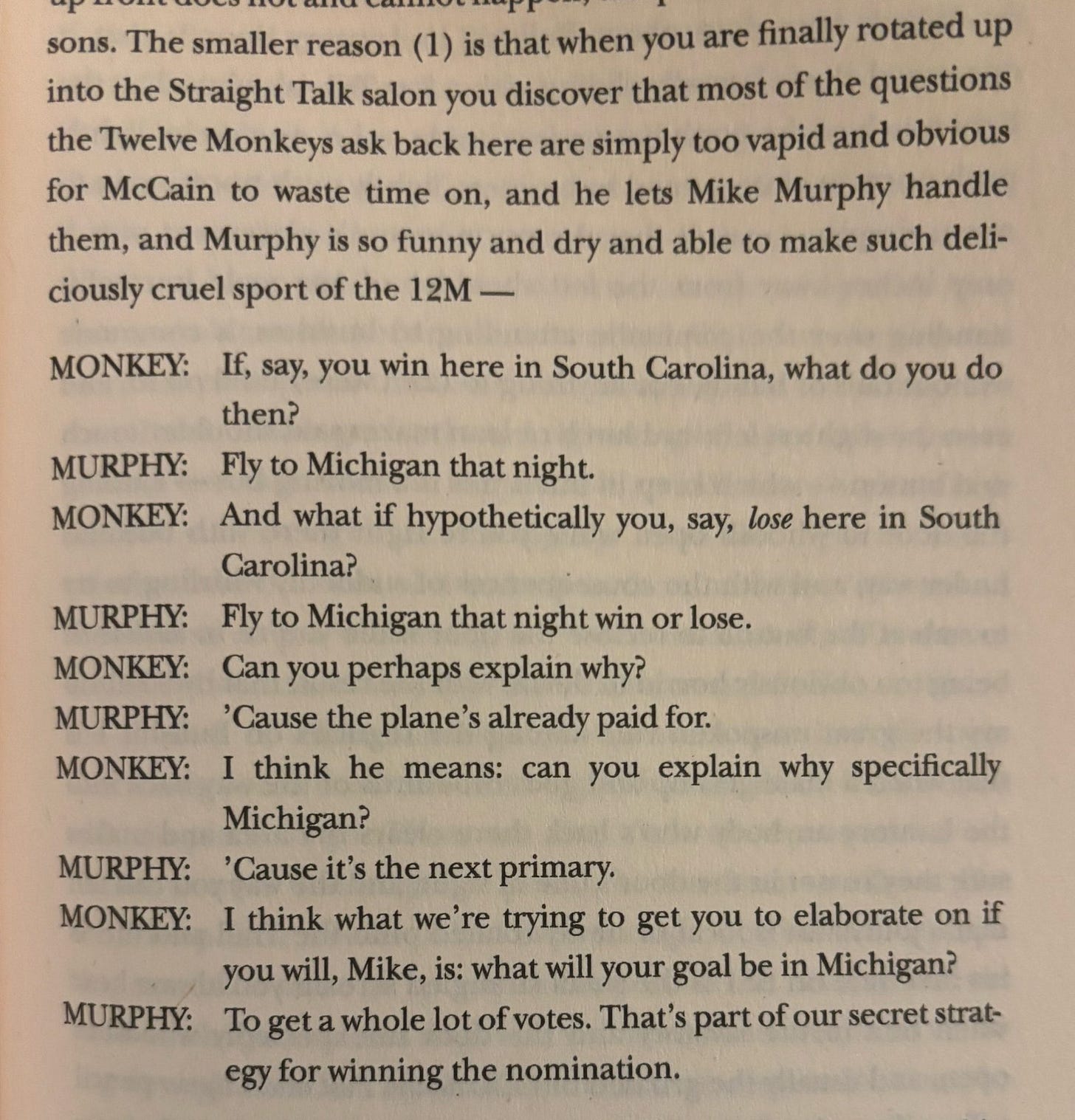

3.1. His description of Mike Murphy in Up, Simba, the full, unedited version of his Rolling Stone article about John McCain’s 2000 presidential campaign.

He’s a short, bottom-heavy man, pale in a sort of yeasty way, with baby-fine red hair on a large head and sleepy turtle eyes behind the same type of intentionally nerdy hornrims that a lot of musicians and college kids now wear. He has short thick limbs and blunt extremities and is always seen either slumped low in a chair or leaning on something. Oxymoron or no, what Mike Murphy looks like is a giant dwarf. Among political pros, he has the reputation of being (1) smart and funny as hell, and (2) a real attack-dog, working for clients like Oliver North, New Jersey’s Christine Todd Whitman, and Michigan’s own John Engler in campaigns that were absolute operas of nastiness, and known for turning out what the NY Times delicately calls “some of the most rough-edged commercials in the business.”

3.2. This comes dozens of pages after the Murphy character has already been introduced through his role and actions, including this scene (where MONKEY is not monkey, obviously, but one of “the most elite and least popular pencils [i.e., print journalists] in the McCain press corps”):

3.3. In the same essay, on John McCain—reproducing the whole massive paragraph because it’s worth reading, including for McCain’s story itself (so: read it):

Here’s what happened. In October of ’67 McCain was himself still a Young Voter and was flying his 26th Vietnam combat mission and his A-4 Skyhawk plane got shot down over Hanoi, and he had to eject, which basically means setting off an explosive charge that blows your seat out of the plane, and the ejection broke both McCain’s arms and one leg and gave him a concussion and he started falling out of the skies over Hanoi. Try to imagine for a second how much this would hurt and how scared you’d be, three limbs broken and falling toward the enemy capital you just tried to bomb. His chute opened late and he landed hard in a little lake in a park right in the middle of downtown Hanoi. (There is still an NV statue of McCain by this lake today, showing him on his knees with his hands up and eyes scared and on the pediment the inscription “McCan — famous air pirate” [sic].) Imagine treading water with broken arms and trying to pull the life vest’s toggle with your teeth as a crowd of North Vietnamese men all swim out toward you (there’s film of this, somebody had a home-movie camera and the NV government released it, though it’s grainy and McCain’s face is hard to see). The crowd pulled him out and then just about killed him. Bomber pilots were especially hated, for obvious reasons. McCain got bayoneted in the groin; a soldier broke his shoulder apart with a rifle butt. Plus by this time his right knee was bent 90 degrees to the side, with the bone sticking out. This is all public record. Try to imagine it. He finally got tossed on a jeep and taken only about five blocks to the infamous Hoa Lo prison — a.k.a. the Hanoi Hilton, of much movie fame — where for a week they made him beg for a doctor and finally set a couple of the fractures without anesthetic and let two other fractures and the groin wound (imagine: groin wound) go untreated. Then they threw him in a cell. Try for a moment to feel this. The media profiles all talk about how McCain still can’t lift his arms over his head to comb his hair, which is true. But try to imagine it at the time, yourself in his place, because it’s important. Think about how diametrically opposed to your own self-interest getting knifed in the nuts and having fractures set without a general would be, and then about getting thrown in a cell to just lie there and hurt, which is what happened. He was mostly delirious with pain for weeks, and his weight dropped to 100 pounds, and the other POWs were sure he would die; and then, after he’d hung on like that for several months and his bones had mostly knitted and he could sort of stand up, the prison people came and brought him to the commandant’s office and closed the door and out of nowhere offered to let him go. They said he could just … leave. It turned out that US Admiral John S. McCain II had just been made head of all naval forces in the Pacific, meaning also Vietnam, and the North Vietnamese wanted the PR coup of mercifully releasing his son, the baby-killer. And John S. McCain III, 100 pounds and barely able to stand, refused the offer. The US military’s Code of Conduct for Prisoners of War apparently said that POWs had to be released in the order they were captured, and there were others who’d been in Hoa Lo a much longer time, and McCain refused to violate the Code. The prison commandant, not at all pleased, right there in his office had guards break McCain’s ribs, rebreak his arm, knock his teeth out. McCain still refused to leave without the other POWs. Forget how many movies stuff like this happens in and try to imagine it as real: a man without teeth refusing release. McCain spent four more years in Hoa Lo like this, much of the time in solitary, in the dark, in a special closet-sized box called a “punishment cell.” Maybe you’ve heard all this before; it’s been in umpteen different media profiles of McCain this year. It’s overexposed, true. Still, though, take a second or two to do some creative visualization and imagine the moment between John McCain’s first getting offered early release and his turning it down. Try to imagine it was you. Imagine how loudly your most basic, primal self-interest would cry out to you in that moment, and all the ways you could rationalize accepting the offer: What difference would one less POW make? Plus maybe it’d give the other POWs hope and keep them going, and I mean 100 pounds and expected to die and surely the Code of Conduct doesn’t apply to you if you need a doctor or else you’re going to die, plus if you could stay alive by getting out you could make a promise to God to do nothing but Total Good from now on and make the world better and so your accepting would be better for the world than your refusing, and maybe if Dad wasn’t worried about the Vietnamese retaliating against you here in prison he could prosecute the war more aggressively and end it sooner and actually save lives so yes maybe you could actually save lives if you took the offer and got out versus what real purpose gets served by you staying here in a box and getting beaten to death, and by the way oh Jesus imagine it a real doctor and real surgery with painkillers and clean sheets and a chance to heal and not be in agony and to see your kids again, your wife, to smell your wife’s hair…. Can you hear it? What would be happening inside your head? Would you have refused the offer? Could you have? You can’t know for sure. None of us can. It’s hard even to imagine the levels of pain and fear and want in that moment, much less to know how we’d react. None of us can know.

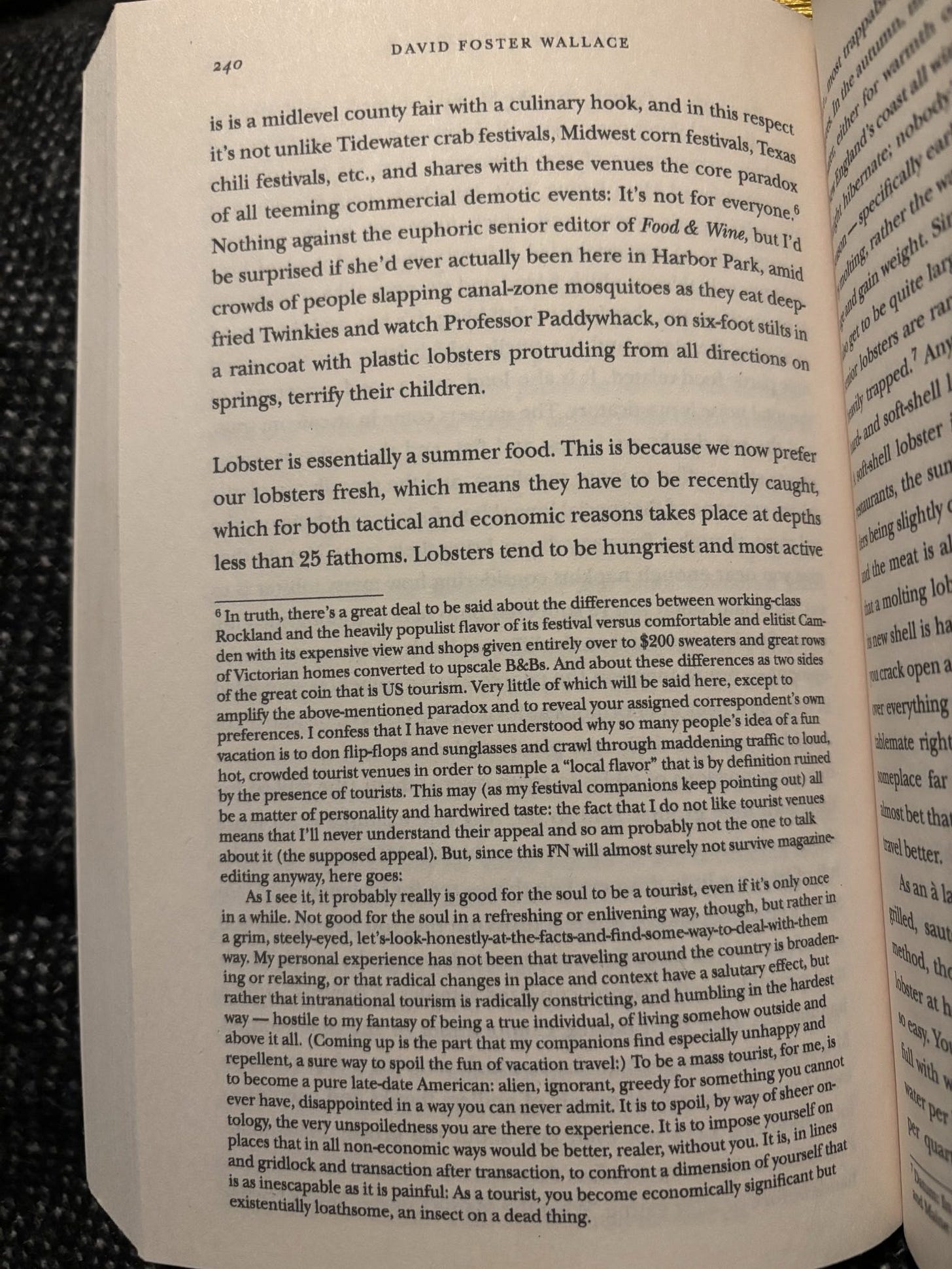

3.4. Different topic, different essay: his footnote on mass tourism in Consider the Lobster, reproduced here as a photo of the printed book, which somehow makes it even more footnoty:

3.5. On yet another topic, Big Red Son offers a critical perspective on the adult industry and its protagonists, and contains many gems such as:

The adult industry is vulgar. Would anyone disagree? One of the AVN Awards’ categories is “Best Anal Themed Feature”; another is “Best Overall Marketing Campaign — Company Image.” Irresistible, a 1983 winner in several categories, has been spelled Irresistable in Adult Video News for fifteen straight years. The industry’s not only vulgar, it’s predictably vulgar. All the clichés are true. The typical porn producer really is the ugly little man with a bad toupee and a pinkie-ring the size of a Rolaids. The typical porn director really is the guy who uses the word class as a noun to mean refinement. The typical porn starlet really is the lady in Lycra eveningwearwith tattoos all down her arms who’s both smoking and chewing gum while telling journalists how grateful she is to Wadcutter Productions Ltd. for footing her breast-enlargement bill. And meaning it. The whole AVN Awards weekend comprises what Mr. Dick Filth calls an Irony-Free Zone.

But of course we should keep in mind that vulgar has many dictionary definitions and that only a couple of these have to do w/ lewdness or bad taste. At root, vulgar just means popular on a mass scale. It is the semantic opposite of pretentious or snobby. It is humility with a comb-over. It is Nielsen ratings and Barnum’s axiom and the real bottom line. It is big, big business.

3.6. And finally, on Lynchianness, from his essay on David Lynch:

AN ACADEMIC DEFINITION of Lynchian might be that the term "refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former's perpetual containment within the latter." But like postmodern or pornographic, Lynchian is one of those Porter Stewart-type words that's ultimately definable only ostensively-i.e., we know it when we see it. Ted Bundy wasn't particularly Lynchian, but good old Jeffrey Dahmer, with his victims' various anatomies neatly separated and stored in his fridge alongside his chocolate milk and Shedd Spread, was thoroughgoingly Lynchian. A recent homicide in Boston, in which the deacon of a South Shore church reportedly gave chase to a vehicle that bad cut him off, forced the car off the road, and shot the driver with a highpowered crossbow, was borderline Lynchian. A Rotary luncheon where everybody's got a comb-over and a polyester sport coat and is eating bland Rotarian chicken and exchanging Republican platitudes with heartfelt sincerity and yet all are either amputees or neurologically damaged or both would be more Lynchian than not. A hideously bloody street fight over an insult would be a Lynchian street fight if and only if the insultee punctuates every kick and blow with an injunction not to say fucking anything if you can't say something fucking nice.

That’s it. Hope this gets more people into DFW.